10-03-2013 08:33 AM

Spanish banks: Health check

OVER a year has passed since the euro zone’s “men in black” descended on Madrid to extend a loan to bail out the country’s troubled lenders. The ability to draw money from that pot expires in January; the European Commission has said there is a good chance Spain won’t need an extension. How much progress has really been made?

A lot. The IMF says reform of Spanish banking is nearly complete. Following exhaustive stress tests, banks have been recapitalised using, among other sources of cash, €41.3 billion ($56 billion) out of a possible €100 billion euro-zone pot. A bad bank, Sareb, has been set up to house their toxic property assets. Provisions now cover a large chunk of the system’s dud loans, with more on the way after the Bank of Spain forced banks to come clean on the state of refinanced loans. Spain’s bloated banking sector has shrunk from 50 lenders to 12. Deposits are stabilising; banks have reduced their reliance on funding from the European Central Bank (ECB).

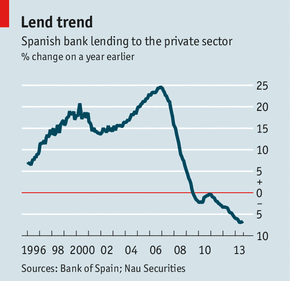

Some worries remain. Small businesses in Spain still face higher loan rates than elsewhere in Europe. Credit is shrinking by about 7% year on year (see chart). But that is to be expected given the indebtedness of the private sector and weak economic conditions, says Daragh Quinn of Nomura. The Bank of Spain’s deputy governor says the economy must recover in order for credit to flow, not the other way around.

One problem is that despite the extensive clean-up, property continues to clog bank balance-sheets. Spain’s largest banks are sitting on €159.4 billion of property loans and assets, according to Goldman Sachs, an amount that has barely budged since 2011 thanks to a moribund housing market. House prices have already fallen by more than 30% from their peak, but are expected to fall further. Private equity is starting to buy property-management arms from the banks, a good sign. But Credit Suisse reckons the banks need another €23.7 billion of provisions against bad loans over the next two-and-a-half years.

Bankers also complain that they are being hit by wave after wave of regulation. In response their instinct is to shrink their risk-weighted assets and hoard capital at the expense of lending. To avoid exacerbating the credit crunch, the IMF says banks should continue to limit dividends and should also issue equity. Banco Sabadell, a mid-sized lender, recently raised €1.4 billion to bolster its finances.

It is not yet clear how much more capital banks will need. The ECB’s asset-quality review, an assessment of euro-zone banks’ balance-sheets that is due to take place next year, will help reveal the extent of any shortfall. Since the ECB has hired the same consultant—Oliver Wyman—that oversaw the Spanish stress tests, hopes are high that it will not turn up nasty surprises.

Much depends on the taxman. Spanish banks have over €50 billion of deferred tax assets (DTAs), some of which are generated when banks make losses that can be offset against future tax bills. DTAs account for about 37% of Spanish banks’ core tier-1 capital, but do not count as core capital under the new Basel 3 global banking rules. In Italy the government agreed to swap DTAs for tax credits, which do count under Basel 3, under certain circumstances. Spanish lenders are hoping for the same.

Spain still has much to do, including a reform aimed at reducing the influence of the savings-banks foundations, and the sale of two nationalised lenders. But one problem it cannot solve on its own. Just as Spain is exposed to its banks, its banks are exposed to Spain. The government debt that listed institutions hold is 2.3 times their tangible equity, reckons BNP Exane. Without a full euro-zone banking union, including a common fiscal backstop to help resolve banks that get into trouble, that worrying bond cannot be broken.

Continue Reading >>

Results 1 to 1 of 1

-

10-04-2013, 05:07 AM #1

News: Spanish banks: Health check

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote